The History and Future of Socket-level Multiplexing

Multiplexing (sometimes called muxing) has a long history of innovation in telecommunications. In 1875, Edison figured out how to transmit four separate telegraph lines over a single wire. In 1910, multiplexing technology was brought to telephony. Within 30 years the Bell System could multiplex 2,400 channels over a single cable. Then in the 1960s we got packet switching, a kind of unlimited multiplexing, which led to computer networking and Internet protocols.

I think of layered protocols and packet switching as "virtualized" multiplexing. Every layer provides a new medium or virtual transport for more protocols to operate, all over the same physical medium. Ethernet allows IPX, IP, and other packets. IP then allows UDP, TCP, and other packets. TCP allows HTTP, SSH, and so on.

The layers nearly end at TCP and UDP because these two protocols provide most of what any programmer would need to make two programs talk. This was more or less set in stone in the 1980s when Unix introduced the socket API , which has been the de facto standard interface for network programming ever since.

This API layer is where you get "application protocols" like FTP, Telnet, DNS, and so many others. TCP, UDP, and the layers below were typically concerned with just getting bytes from one point to another. Application protocols introduced more specific interactions like request-reply, such as with HTTP. Some, like SSH and DNS, became rather multifaceted protocols to serve their domain with many different flows and message types. Rarely would you find an application protocol multiplexed to provide a generic transport for another.

An early exception was SSH. One of the reasons SSH fascinates me is that it was designed for many uses and breaks down into its own set of layers and internal protocols, almost mirroring TLS, TCP, and UDP.

First, SSH establishes an authenticated and encrypted line, similar to TLS. Then you have two very generic ways to communicate over this line. You can send "request" messages that may or may not get a response, similar to use cases of UDP. Or you can establish "channels" that were bidirectional streams just like TCP.

From there, SSH defines how to use these requests and channels as primitives to set up remote shells. But besides that, you could also forward TCP connections, which worked by bridging a TCP socket with an SSH channel, "tunneling" the TCP connection through the SSH connection.

If you've ever used Ngrok to open a public endpoint to a localhost server, you may not know it was one of several clones of a tool I made in 2010 called localtunnel . The original localtunnel was just a wrapper around SSH, literally using OpenSSH on the server side.

So SSH was one of the earliest application level protocols designed to further multiplex its transport protocol. The next protocol to multiplex at the application/socket level was HTTP/2. It was introduced in 2015, which is still quite recent, but 20 years after SSH.

HTTP has become a new de facto API, like Unix sockets did. What was originally used to just download files into the browser has been co-opted and repurposed. As people started building more and more complex applications in the browser and with the emergence of web APIs, HTTP evolved into a sort of "do everything" protocol.

In 2012, Google started an effort to design a more efficient HTTP with what they called SPDY, which they were able to test end-to-end in Chrome without people even knowing. After proving its improved performance and cost saving benefits, SPDY basically became HTTP/2. They did a number of things to make it more efficient, but the core idea was multiplexing.

HTTP/2 was more or less HTTP, but over newly introduced multiplexed "streams" similar to normal TCP connections. This makes them roughly the equivalent of SSH "channels". At least at one point, Ngrok used a subset of HTTP/2 as their muxing protocol the same way localtunnel used SSH.

Both HTTP/2 and SSH do more than multiplexing, and usually aren't thought of specifically for muxing. Most library implementations don't expose the lower level multiplexing primitives. SSH at least has clear separation in its specification, where multiplexed channels are a specific and independent layer of the protocol architecture.

After spending so much time with these multiplexing protocols, I noticed something. Most other application protocols also did something similar to multiplexing without realizing.

For example, any request-reply protocol that allows more than one request over a connection is "multiplexing" each request and reply pair. A request and response will often get a shared ID so they can be correlated as other requests and responses can be sent in the meantime. This is the heart of any muxing protocol!

I've found implementing RPC or any request-reply over a muxing API not only simplifies the protocol, but opens up the ability to also stream or tunnel other protocols on the same connection. You could "attach" a tunneled database connection with an RPC response.

Working with muxed streams over a single connection gives me a similar feeling to discovering green threads for the first time. Suddenly, streams between the same two points are so cheap and lightweight you can think about using them in totally different ways.

I now believe a socket API with muxing builtin is a better base layer and API for designing application protocols. I was validated when Google pushed multiplexing into QUIC .

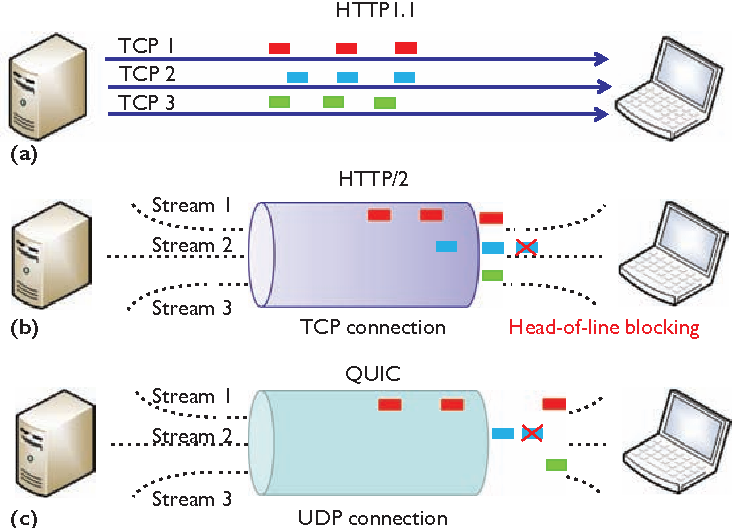

If Google could redesign HTTP, why not also TCP+TLS? Their experience with SPDY started them down a path to reduce the overhead of TLS and TCP session establishment even more by creating a more efficient kind of encrypted TCP over UDP. Built into this layer is stream muxing that would not suffer from head of line blocking .

It's taken nearly 10 years for QUIC to be refined and adopted in the wild and we're basically there. There's even a new browser API in the works called WebTransport .

In the meantime, I started designing protocols on the assumption of having a muxing layer directly beneath. Eventually, that would be QUIC, but as a stopgap, what would it be? Remember, there haven't been any standard TCP muxing protocols.

I considered what Ngrok did with a stripped down HTTP/2, but then I realized... SSH has been around a lot longer. SSH is known to work on nearly every platform and is trusted by basically everybody. Best of all, the SSH muxing layer is simpler and more straightforward than HTTP/2.

So I literally took the muxing chapter of the SSH spec, cut out a couple of SSH specific identifiers, stripped it down to just the channels, and I've been using it for the past 5 years. It's called qmux .

The great thing is that even with QUIC available, qmux can be used over any streaming transport and provide the same foundation for higher level protocols built on muxing. Whether the transport is WebSocket or stdio, as long as it can reliably transport ordered byte streams, qmux drops right in. Protocols built on it will translate easily to QUIC.

I'm only releasing this now because it might not have made sense without all this context or more awareness of QUIC. The banality of a brand new subset of a 25 year old protocol does not escape me, but it's the shift in perspective that brings potential. In that way it's similar to webhooks!

If nothing else, I hope people use this story as inspiration to think about using multiplexing to design better, simpler application protocols. Even if for some reason QUIC isn't the future, you now have qmux !

For more great posts like this sent directly to your inbox and to find out what all I'm up to, get on the list at progrium.com ✌️